At a glance

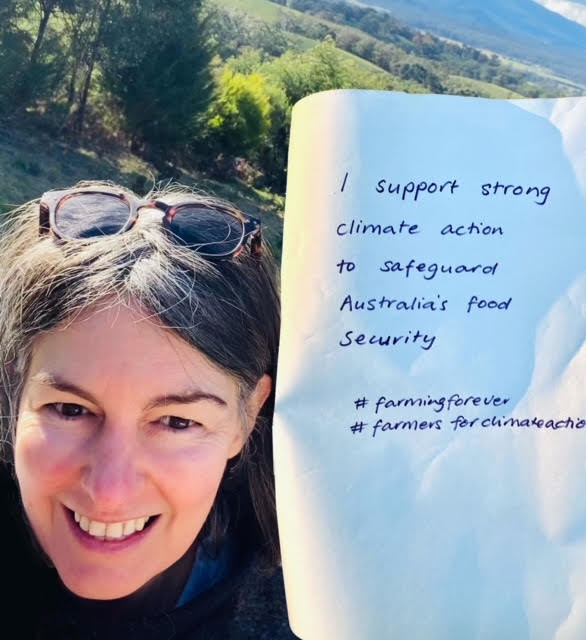

Who: Katherine Wilson

What: Yarra Valley Native

Where: Small-scale regenerative farms on Wurundjeri and Taungurung Country

My partner Conor and I run Yarra Valley Native, supporting a group of mountain pepperberry farms (with side hustles). Our social enterprise model involves growing pepperberry trees in small Victorian land holdings — each currently under 40 acres — in water catchments where rainfall is high enough to grow this increasingly coveted plant.

Mountain pepperberry is a magnificent little tree, native to Tasmania and wet parts of Victoria and New South Wales. Its leaves and berries are deliciously spicy and have powerful antimicrobial properties. They’re coveted for culinary, medicinal, distilling and food preservation use, and demand far outstrips supply. Most current supply is coming from native forests, which is a problem.

We’re growing pepperberry not merely as a high-value cash crop but as a regenerative and forest conservation tool on degraded Wurundjeri and Taungurung land. As an understory crop, pepperberry thrives in slightly acid soils and conditions that some other pioneer plants may not like. Shortly, we’re planning to experiment with swales and plant more on the contours.

We’re also collaborating with First Nations people to regenerate traditional approaches to harvesting. One approach I learned recently from Aunty Kim Wandin is the practice of leaving some pepperberry yield at the top of the tree for the Currawongs, and some at the bottom for the ground. No netting, no hoarding! This approach is the antithesis of the more efficient profit-driven colonial approach, but it’s simpatico with the values we believe will help heal this country.

Luckily, Conor and I are in the privileged position to consider profitability only one of our farms’ aims — the others being social benefit, land regeneration and climate repair. All these involve decolonising the land, and we’re still learning what that means in practical terms. As part of this approach, we hope to share propagation techniques, land and stock with First Nations collaborators. If our collaborators’ success puts us out of business, that’s a win in our eyes. As a criminal lawyer, Conor comes from a social justice background, and I worked for many years as a journalist and academic, so we both have off-farm resources to fall back on, as well as side-hustles from our land. I think rapid adaptability and diversification are key to making intensive small-scale farming secure. With sovereign owners, we hope to pilot a model for other farmers who wish to commit to First Nations reparations.

I can’t remember a time I wasn’t aware of the looming climate crisis and then the impact climate change is having on farmland and forests. I come from a family of broadacre farmers and my father, Geoff Wilson, was agribusiness editor at The Age in the 1980s and an early advocate for climate action. In his time he also edited and wrote for The Weekly Times, Stock & Land and National Farmer, and he started a visionary magazine in the 1970s called Tree Farmer. He published many farming books — among them Agroforestry, co-authored with Rowan Reid.

From what he taught me, monocropping never made sense, and tree farming always seemed an attractive option because it doesn’t involve fixing fences or getting up at 4:30am to milk. The farmers in my family were relentlessly hard-working, and my dad dragged me to more field-days and farm-tours than I appreciated, giving me some idea of the challenges. One of these tours was a visit tof David Holmgren’s property, which motivated me to study permaculture design and become a wwoofer on a few organic farms up in Queensland, before my career in journalism scuppered any farming dreams.

My dad died in Queensland during the first COVID lockdown, before Conor and I could show him how we’re living out his legacy in Victoria. But he left me with the conviction that tree plantations can be the best pathway to resilience. Many can serve as fodder-crops as well as wind-breaks, and most natives serve as an important way to lock up carbon and produce timber, seeds and honey. We’re continuing his vision and his interest in the ways traditional broadacre approaches can be integrated with more intensive small-scale production. He believed both models can be rendered carbon-neutral or carbon-negative with good soil health and judicious land management. That’s the legacy we want to achieve and then pass on. Especially at a time when there’s a kind of urban-rural devolution underway, with so many tree-changers buying up good land.